|

Experimenting with Kreisel

Construction

|

By Sara Mavinkurve |

With more and more aquarists thinking about captive breeding, we are

beginning to face challenges usually reserved for academics and public

aquariums. I found myself facing one such challenge after setting out to raise

the zoea released by my emerald and ruby crabs.

These crustacean larvae are fascinating for their apparent dichotomy in

being surprisingly tolerant of great swings in temperature and salinity, while

at the same time being apparently inept at simply keeping themselves afloat. A

fellow hobbyist told me that he was once able to raise them into the megalopa

stage simply by keeping them in a bucket with an air stone and feeding them

brine shrimp nauplii.

However, I had no such luck. All of my attempts to keep them in smaller

tanks, fish bowls, inverted cones, etc., with air stones for circulation,

ultimately failed. They inevitably sank, collecting at the bottom or in the

corners of the container. At one point I even resorted to constantly rocking

them in my arms in a round fish bowl. This seemed to work for them, but not so

much for me. In those intimate long hours rocking them back and forth to the

enchanting sounds of Green Day and U2, I realized that what they apparently

needed was a constant sweeping current underneath them. The only type of set up

I know to be able to provide this type of circulation is a planktonkreisel.

What is a planktonkreisel?

Planktonkreisels are nothing new. While best known for their use in

housing jellyfish, they can be used to house many different kinds of delicate

marine invertebrates. Researchers and aquaculture facilities have built their

own versions and adaptations of the planktonkreisel to suit their own needs and

ambitions.

And yet, despite the widespread knowledge and use of these types of

units, I was surprised to find a severe lack of public information on exactly

how these units work, much less how to build one at home. After constructing

this one, I later learned that similar kreisels have been built and used by

several public aquariums. Consequently, I was unsure as to if my discussion and

documentation of my own experience wouldn't be redundant.

Not knowing anyone who would know better, I asked Martin Moe if my

experience in designing and constructing this Kreisel was something worth

sharing with the coral list serve (and the aquarist community in general). He

kindly advised me that though the basic design of my Kreisel is not unique, it

is worthwhile for the availability of the materials used and for the

transparency of its construction. Even though very general descriptions of

planktonkreisels and pseudo-planktonkreisels are easily found, publicly

available (and hobbyist accessible) step-by-step instructions for the

construction of any type of planktonkreisel are virtually nonexistent. In this

article, I hope to provide hobbyist accessible step-by-step instructions for the

construction of at least one such unit.

Construction

Having hardly enough space in my city apartment for the aquariums I

already have, I needed to construct a unit that could either fit within my

display tank or in a separate tank small enough to fit on my 6-inch wide

windowsill. Some hobbyists have built small pseudo-planktonkreisels simply by

placing baffles in the corners of a small rectangular tank. The top of the tank

is left open and flat. These set-ups are reported to be successful in some cases

with some types of larvae.

However, remembering how the crustacean larvae seemed to appreciate the

rounded bottom of the fish bowl, I wanted to build something with a curved

bottom and a less exposed top. Ideally, I wanted the unit to also be able to

utilize the filtration and stability of a

much larger tank (such as my display tank).

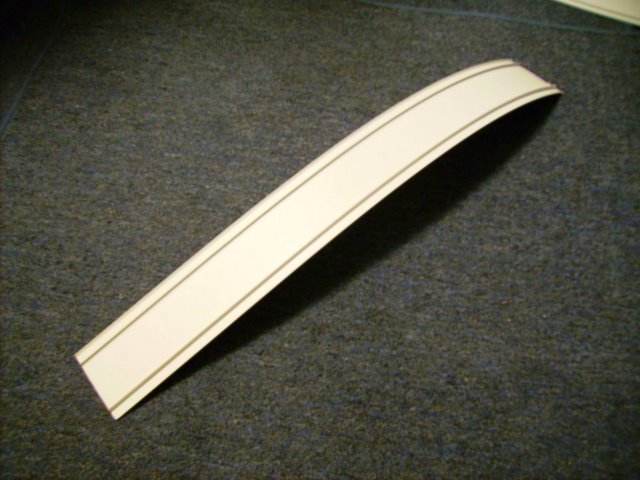

28.5-inch strip of vinyl siding

My first thought was to use a bucket as a circular baffle inside a 5 or

10 gallon tank. I soon realized this wouldn't work for several reasons (one

being that I couldn't find a bucket of the right size, shape or thickness). Next

I thought of using a large piece of PVC piping instead of a bucket. However,

being limited to the inventory of my local hardware stores, I couldn't find a

piece of piping of the right size or shape for the job.

[Note: After sharing my Kreisel with the coral list serve, a marine

biologist, Chris Maupin, told me that he had once made a small Kreisel similar

to mine by placing a piece of PVC piping between two pieces of acrylic.]

Temporarily out of ideas, I wandered around Home Depot hoping for

inspiration when it literally hit me. A piece of vinyl siding slid down from a

rack and collided with my head. As I became increasingly frustrated trying to

push this surprisingly flexible stripe of vinyl back up in its place, it

occurred to me that maybe the hardware gods were trying to tell me something.

Though it seemed like an odd material to use, it was cheap (less than $6 for an

8-foot long, 3.5-inch strip), approximately the right width, and easy to bend

into a circle. It can also be cut with a strong pair of scissors or drilled

through with a hand drill.

I wanted the Kreisel barrel and frame to be able to fit inside a 2.5g

tank (or possibly a 5g tank). I also wanted to be able to fit my hand inside the

barrel of the Kreisel (so that it would be easier to clean and maintain).

Keeping all this in mind, I cut a 28.5-inch long strip of siding and worked it

into a circular barrel. I then used a Dremel saw to carve out two rectangles (to

be two drains) at one end of the vinyl stripe and a slot at the other end (for

water flow into the barrel). The in-flow is approximately 6-inch from one end of

the vinyl. The first drain is approximately 13-inch down the strip from the

in-flow. These measurements might be somewhat flexible.

However, after building 4 of these units (each with a slightly different

positioning of the drain and in-flow), I do believe that the first drain and the

in-flow slot should be positioned such that when the vinyl is bent into a

circle, the first drain and the in-flow are close to being directly across from

each other as possible. In other words, the distance between the first drain and

in-flow should be approximately the diameter of the would-be circle. It seems

that this positioning results in the best, continued circular flow. The second

drain is at the very top of the barrel (to serve as a back-up drain to prevent

the barrel from overflowing should the first drain become clogged). Ideally, the

water level should not ever reach the second drain. Next, I glued a flow

diverter from a Maxijet under the in-flow flap/slot and glued a piece of tubing

into the diverter, using silicone sealant to seal off any gaps.

Tracing the flow diverter

Drilling out the in-flow slot

Drilling out the drains

Gluing tubing to the flow

diverter

To screen the drains, I cut two rectangular pieces of rotifer sieve mesh

(65 micron) and used epoxy to seal these over the drains. Once this epoxy was

well set, I duck-taped the ends of the vinyl strip together with a gap between

the two ends just wide enough to allow me to reach my hand into the barrel. I

then positioned the barrel between two rectangular pieces of acrylic. I measured

out the two pieces of acrylic to fit (width-wise) inside a 2.5g tank and tall

enough to cover the top of the barrel and the tubing. I cut a corner off one

piece of acrylic (on the side of the drain) to allow room for the pump.

The next challenge was joining the vinyl to the acrylic. I won't recount

all my embarrassing failed attempts at this. Fortunately, I ultimately

discovered that enough waterproof two-part epoxy will do the trick. I held

everything in place with duck tape while applying the epoxy. One of the nice

things about epoxy is that it dries very smooth. Thus, it's also an easy way to

cover up any rough edges.

Positioning the flow diverter

Securing flow diverter to in-flow

slot

Gluing the mesh over the drain

Generous glazing with epoxy just

to be certain there are no leaks

Lastly for the barrel, to protect the larvae and to better direct flow,

I made a flow directing shield out of more vinyl siding and glued it over the

Maxijet flow diverter. I'd like to note here that the order in which I completed

some of these steps might not be the easiest way to assemble this unit. For

example, it might be easier to add the shield after joining the barrel to the

acrylic. I don't think it matters much what order one cares to assemble things

so long as the end result is the same. Also, ideal dimensions of the barrel and

acrylic frame will entirely depend on where and how you plan to use the Kreisel.

Installation

After all was set and done, I was able to slide the whole thing into a

2.5g tank with a small Rio pump suctioned to the lower left-hand corner of the

front panel of the tank. I connected more tubing to the Rio pump, reaching up

and connecting to the tubing from the barrel via a flow valve. The flow valve is

important because you'll need to be able to control flow into the barrel. Flow

out of the barrel can change as the drain becomes clogged with food (or other

small particles) in between cleanings.

Holding things in place with duck

tape

Adding "bumpers" for in display

tank set up, using split airline tubing

The setup as a whole works a bit like a sump inside of a tank. You have

to adjust the flow so that the flow through the drain matches the flow into the

barrel. This allows the water level in the barrel to be above the water level in

the holding tank without overflowing the barrel. The water level in the barrel

could also be set to match the water level in the holding tank (whatever works

best for your needs). To use the unit in any tank taller than the height from

the bottom of the acrylic frame to the top of the barrel, a hanger is needed. I

fashioned a simple hanger out of spare pieces of acrylic. Split airline tubing

can be used to make 'bumpers' by wrapping it over the edges of the acrylic.

In use

Some of the things I like about this particular Kreisel are that it is

very small; dissembles and cleans easily; and appears to lose less water to

evaporation than more open-topped units. It's lightweight, compact and can be

used in any size tank.

Having built several of these units now (and gone through at least 20

tubes of epoxy), I've learned a little with each re-build. The use of 65 micron

screening, the shape of the drains, and the addition of the second 'safety'

drain are details I learned to be important after testing the units with actual

crustacean larvae (zoea stages of Mithrax sculptus larvae).

Set up in a 2.5g tank

Set up in my 65g display tank

Initially I had used brine shrimp netting to screen a single circular

shaped drain. This drain design failed for two reasons: 1) circular drains

create screened 'divots' which are apparently more of a challenge for larvae to

roll over, and 2) while crustacean larvae do not pass through brine shrimp

netting, for whatever reason, they apparently get stuck in it quite easily. I

quickly rebuilt the unit using rectangular drains screened with rotifer mesh.

The remaining larvae did greatly appreciate the adjustments. At last I could

sleep through the night without having to worry that I'd wake up to find them

settled at the bottom of the unit or plastered against brine shrimp netting.

Unfortunately, they ultimately perished when I forgot to lower the water

level before plunging my hand into the barrel to clean the drains. My hand and

forearm displaced more water than my 'safety' drain could compensate for and the

larvae spilled out into the display tank where they quickly became fish food. Of

course, this became just another lesson learned.

I hope that other hobbyists will experiment with this design and attempt

to use it with other types of larvae. The greatest reward would be able to use

this set-up to successfully raise crustacean larvae past the critical megalopa

stage of development. I'm confident that it can and eventually will. Hopefully,

it will not only for Mithrax sculptus larvae, but also for other types

of delicate crustacean larvae.

|