|

The seafood we offer to predatory pets like large fishes, axolotls and

predatory turtles cannot always compete with their natural diet in terms of

variation and freshness.

Because we mostly feed our pets frozen foods, we need to consider any

biochemical differences between their natural diet and their captive diet. The

freezing and thawing processes can result in deficiency diseases in the long

run, and if this is exacerbated by poorly chosen food items, the result is that

our pets will enjoy a shortened lifespan.

In particular, one problem often discussed in the context of feeding

predatory animals is the presence of the enzyme Thiaminase in many types of fish

and invertebrates. While strong and often controversial opinions on this topic

have been voiced among pet owners, there is a distinct lack of solid

information. It is the intention of this article to summarize what is known

about Thiaminase and the related deficiency disease, which can be relevant for

pet fish nutrition.

"Predatory fishes like this moray eel need a

fishy diet, but not all foods available in trade are equally safe with

regard to their Thiaminase content."

What is Thiaminase?

Thiaminase is an enzyme, a chemical compound that destroys or

inactivates thiamine. Thiamine is an important vitamin also known as Vitamin B1.

There is not just one type of Thiaminase, but several different ones, some of

which can be produced by bacteria, fungi, plants and potentially animals.

The lack of Vitamin B1 in humans is called beriberi.

Thiamine Deficiency Syndrome and its symptoms

Vitamin B1 (also known as thiamine, thiamine

hydrochloride, and in older text books, as aneurine

hydrochloride) is an essential nutrient for most animals. It is a

colorless and water soluble chemical that helps to convert carbohydrates into

glucose. It is particularly important for the correct functioning of the nervous

system. A lack of Vitamin B1 is called a Thiamine Deficiency Syndrome.

Symptoms of this syndrome are well known from several commercially

important fish groups and can be confirmed using appropriate biochemical tests.

Flatfish fed exclusively with Thiaminase-rich clams suffer and die from

paralysis and related physical shocks. Eels show a trunk-winding syndrome and

hemorrhages along the base of the fins (similar symptoms have been reported from

moray husbandry, too). Salmonids show nervous disorders, poor appetite, poor

growth and jumpiness (again, similar things have observed among a variety of

ornamental fish species). Skin congestion and haemorrhage have been reported

from carp and other cyprinids. In general then, excessive amounts of Thiaminase

are connected with symptoms of sickness that include poor growth, loss of

appetite, abdominal swelling and hemorrhage, loss of equilibrium, convulsions,

muscle atrophy and a weak immune system.

While it has not yet been scientifically proven that pet fish suffering

from the above mentioned symptoms have Thiamine Deficiency Syndrome, the

parallels with their food fish relatives are striking. The problems of

Thiaminase are now well known in the professional fields of animal nutrition

(e.g. fish farms), but so far this information has not been widely taken up by

aquarists and pet owners. But it is clear that those hobbyists keeping large

predatory fish and other carnivorous animals need to be familiar with the

problem of Thiamine Deficiency Syndrome, and use that information to make

sensible choices when selecting food for their livestock.

Aren't Thiaminase containing fish eaten in the wild?

Yes, they are, and this can cause predatory fish massive problems. The

offspring of salmon from the Baltic Sea -- which apparently feed mostly on

Thiaminase-rich herring and relatively little food that contains high levels of

Vitamin B1 -- were found to suffer from a condition called Reproduction Disorder

M74. This was later identified as being simply one particular form of Thiamine

Deficiency Syndrome. The eggs produced by adult salmon were provided with very

little thiamin, and the fry that emerged almost all died soon after hatching.

Comparable problems have been found among Salmonids in the Great Lakes of North

America, and this has been hypothesized to be related to a diet containing a

large proportion of alewives, another type of Thiaminase-rich fish.

However, most of the time predatory fishes maintain a kind of balance

between those prey fish rich in Thiaminase and those fish rich in Vitamin B1. As

long as the predator has a reasonably varied diet, it should get enough Vitamin

B1 to stay healthy. It should be mentioned that in the examples of the sick

Salmonids from the Baltic, the key problem was that they were not eating a

varied diet, but mostly consuming just one type of prey.

The big problem for captive fish is that they are fed frozen fish.

Thiaminase is not destroyed by freezing, and over time will break down whatever

Vitamin B1 is present in the frozen fish. The longer the fish is stored, the

less Vitamin B1 it will contain. Furthermore, any fish fed such frozen fish will

be consuming the Thiaminase, and that will destroy some of the Vitamin B1 it

already has. Making things even worse, freezing and thawing both break down some

of the Vitamin B1 content of food as well.

While freezing does not destroy Thiaminase, heating it will. This is why

cooked fish is not dangerous with regard to Thiaminase for human or animal

nutrition. From the perspective of a fishkeeper, the big drawback to cooking

food is that heating destroys a lot of the useful nutrients as well. While

omnivorous humans compensate for that by eating a varied diet containing both

raw and cooked plant and animal foods, piscivorous fish have no such option.

They cannot be fed cooked fish and expected to stay healthy.

At least some types of live feeder fish will contain more Vitamin B1

than frozen foods, but the downside here is that the convenience of live foods

is accompanied by a major risk of introducing pathogenic microorganisms such as

Mycobacteria and endoparasites. Feeder fish are also expensive compared with

frozen foods, and as will be described shortly, many of the types of feeder fish

widely sold contain a great deal of Thiaminase anyway, dramatically reducing

their usefulness.

Which fish and other food of aquatic origin contains Thiaminase?

A common generalisation often made by aquarists is that marine fish

don't contain much Thiaminase while freshwater fish do. This is not the case at

all.

From my review of the literature, of the 32 species of freshwater fish

tested, 18 of them were found to contain Thiaminase. Among the 61 marine fish

tested, 32 were found to contain Thiaminase. In other words, 56% of the

freshwater fish examined contained Thiaminase compared with 51% of the marine

fish species. If there is a difference between freshwater fish and marine fish

in terms of Thiaminase content, any such difference appears to be rather small.

Among the food fish families consumed by man, species that contain

Thiaminase include minnows, carps, herrings, anchovies, goatfishes and snappers.

Many different invertebrates have also been found to contain Thiaminase,

including mussels, clams and shrimps/prawns such as those in the genus

Penaeus, sometimes in even higher concentrations than those found in fish.

In contrast several groups of fish have been generally found to be free

of Thiaminase, including North American sunfishes, flounders, cods and croakers.

"Bivalves such as clams can are a good food within a varied diet, but many

contain a lot of Thiaminase and

should not be used exclusively; some however, notably cockles, contain

little Thiaminase and are consequently a better all-around food for

mollusk-feeding predators such as pufferfish."

Thiaminase content review

The data on Thiaminase content comes from various sources, mostly from

the National research council (1982), Deutsch & Hasler (1943), Greig &

Gnaedinger (1971) and Hilker & Peter (1966); see also the literature list at the

end of the article. The lists are far from complete, but most of the usually

marketed and so far examined species are enlisted. Although primarily based on

coldwater food fish and invertebrates, Thiaminase content information exists for

several tropical species widely marketed, and these been included accordingly.

Species that contain Thiaminase

Freshwater fish

Family Cyprinidae (Minnows or carps):

Common bream (Abramis brama)

Central stoneroller (Campostoma anomalum)

Goldfish (Carassius auratus)

Common carp (Cyprinus carpio)

Emerald shiner (Notropis atherinoides)

Spottail shiner (Notropis hudsonius)

Rosy red, Fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas)

Olive barb (Puntius sarana)

Family Salmonidae (Salmonids):

Lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis)

Round whitefish (Prosopium cylindraceum)

Family Catostomidae (Suckers):

White sucker (Catostomus commersonii)

Bigmouth buffalo (Ictiobus cyprinellus)

Family Ictaluridae (North American freshwater catfishes):

Brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus)

Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus)

Other families:

Bowfin (Amia calva) - family Amiidae (Bowfins)

Burbot (Lota lota) - family Lotidae (Hakes and burbots)

White bass (Morone chrysops) - family Moronidae (Temperate

basses)

Rainbow smelt (Osmerus mordax) - family Osmeridae (Smelts)

Loach, Weatherfish (Misgurnus sp.) - family Cobitidae (Loaches)

Brackish (freshwater to marine) fish

Family Clupeidae (Herrings):

Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus)

Gizzard Shad (Dorosoma cepedianum)

Other families:

Sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) - family Petromyzontidae

(Lampreys)

Fourhorn Sculpin (Triglopsis quadricornis) - family Cottidae

(Sculpins)

Salmon (sp. indet., processed and salted, probably Oncorhynchus

sp.) - family Salmonidae (Salmonids)

Marine fish

Family Engraulidae (Anchovies):

Broad-striped anchovy (Anchoa hepsetus)

Californian anchovy (Engraulis mordax)

Goldspotted grenadier anchovy (Coilia dussumieri)

Family Clupeidae (Herrings):

Atlantic herring (Clupea harrengus)

Atlantik menhaden (Brevoortia tyrannus)

Gulf menhaden (Brevoortia patronus)

Razor belly sardine (Harengula jaguana)

Sauger (Harengula jaguana)

Family Scombridae (Mackerels, tunas, bonitos):

Chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus)

Skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis)

Yellowfin tuna (Neothunnus macropterus)

Family Lutjanidae (Snappers):

Green jobfish (Aprion virescens)

Ruby snapper (Etelis carbunculus)

Crimson jobfish (Pristipomoides filamentosus)

Family Carangidae (Jacks):

Giant trevally (Caranx ignobilis)

Doublespotted queenfish (Scomberoides lysan)

Bigeye scad (Selar crumenophthalmus)

Family Mullidae (Goatfishes):

Red Sea goatfish (Mulloidichthys auriflamma)

Yellowstripe goatfish (Mulloidichthys samoensis)

Manybar goatfish (Parupeneus multifasciatus)

Other families:

American butterfish (Peprilus triacanthus) - family

Stromateidae (Butterfishes)

Southern ocellated moray (Gymnothorax ocellatus) - family

Muraenidae (Moray eels)

Bonefish (Albula vulpes) - family Albulidae (Bonefishes)

Milkfish (Chanos chanos) - family Chanidae (Milkfish)

Common dolphinfish (Coryphaena hippurus) - family Coryphaenidae

(Dolphinfishes)

Hawaiian flagtail (Kuhlia sandvicensis) - family Kuhliidae

(Aholeholes)

Black cod (sp. indet.) - family Moridae (Morid cods)

Flathead mullet (Mugil cephalus) - family Mugilidae (Mullets)

Sixfinger threadfin (Polydactylus sexfilis) - family

Polynemidae (Threadfins)

Regal parrot (Scarus dubius) - family Scaridae (Parrotfishes)

Swordfish (Xiphias gladius) - family Xiphiidae (Swordfish)

Invertebrates

Bivalves:

Ocean quahog (Artica islandica)

Clam (Tellina spp.)

Cherrystone, Chowder, Steamer clams (family Veneridae)

Pigtoe mussel (Pleurobema cordatum)

Scallop (Pecten grandis)

Hawaiian clam (sp. indet.; extremely high in thiaminase)

Blue mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis)

Gastropods:

Limpet (Helcioniscus sp.)

Cephalopods:

Hawaiian flying squid (Nototodarus hawaiiensis)

Crustaceans:

Prawn, Tiger shrimp (Penaeus spp.)

"The flesh of this Brazilian ocellated moray Gymnothorax ocellatus

contains thiaminase. Makes a better pet fish than food fish, anyway!"

Species that do not contain

thiaminaseFreshwater fish

Family Centrarchidae (North American Sunfishes):

Largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides)

Northern rock bass (Ambloplites rupestris)

Northern smallmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieu)

Blue gill (Lepomis macrochirus)

Black crappie (Pomoxis nigromaculatus)

Pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus)

Family Percidae (Perches):

Yellow perch (Perca flavescens)

Walleye (Sander vitreus)

Family Salmonidae (Salmonids):

Bloater (Coregonus hoyi)

Lake trout (Salvelinus namaycush)

Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)

Other families:

Ayu (Plecoglossus altivelis) - family Plecoglossidae (Ayu fish)

Longnose gar (Lepisosteus osseus) - family Lepisosteidae (Gars)

Northern Pike (Esox lucius) - family Esocidae (Pikes)

Brackish (freshwater to marine) fish

Family Salmonidae (Salmonids):

Cisco, Lake herring (Coregonus artedi)

Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar)

Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch)

Sea trout (Salmo trutta)

Other families:

Common eel (Anguilla anguilla) - family Anguillidae (True eels)

Pond smelt (Hypomesus olidus) - family Osmeridae (Smelts)

Marine fish

Family Pleuronectidae (Righteye flounders):

Winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus)

Winter flounder, Lemon sole (Pseudopleuronectes americanus)

American plaice (Hippoglossoides platessoides)

Yellowtail flounder (Limanda ferruginea)

Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus)

European plaice (Pleuronectes platessa)

Family Gadidae (Cods and haddocks)

Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua)

Haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus)

Saithe, Pollock (Pollachius spp.)

Family Sciaenidae (Drums or croakers):

Atlantic croaker (Micropogonias undulates)

Southern kingfish (Menticirrhus americanus)

Spot croaker (Leiostomus xanthurus)

Silver seatrout (Cynoscion nothus)

Sand weakfish (Cynoscion arenarius)

Family Carangidae (Jacks):

Greater amberjack (Seriola dumerilii)

Yellowtail scad (Atule mate)

Mackerel scad (Decapterus pinnulatus)

Family Labridae (Wrasses):

Cunner (Tautogolabrus adspersus)

Tautog (Tautoga onitis)

Family Scombridae (Mackerels, tunas, bonitos):

Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus)

Kawakawa (Euthynnus affinis)

Other families:

Tusk (Brosme brosme) - family Lotidae (Hakes and burbots)

Largehead hairtail (Trichiurus lepturus) - family Trichiuridae

(Cutlassfishes)

Piked dogfish (Squalus acanthias) - family Squalidae (Dogfish

sharks)

Hake (Urophycis spp.) - family Phycidae (Phycid hakes)

Inshore lizardfish (Synodus foetens) - family Synodontidae

(Lizardfishes)

Mullet (Mugil spp.) - family Mugilidae (Mullets)

Scup, Southern porgy (Stenotomus chrysops) - family Sparidae

(Porgies)

Ocean perch, redfish (Sebastes marinus) - family Sebastidae

(Rockfishes)

Black seabass (Centropristis striata) - family Serranidae (Sea

basses and Groupers)

Hardhead sea catfish (Ariopsis felis) - family Ariidae (Sea

catfishes)

Searobin (Prionotus spp.) - family Triglidae (Searobins)

Silver hake (Merluccius bilinearis) - family Merlucciidae

(Merluccid hakes)

Eyestripe surgeonfish (Acanthurus dussumieri) - family

Acanthuridae (Surgeonfishes)

Atlantic blue marlin (Makaira nigricans) - family Istiophoridae

(Billfishes)

Blotcheye soldierfish (Myripristis berndti) - family

Holocentridae (Squirrelfishes, soldierfishes)

Glasseye (Heteropriacanthus cruentatus) - family Priacanthidae

(Bigeyes or catalufas)

Great barracuda (Sphyraena barracuda) - family Sphyraenidae

(Barracudas)

Invertebrates

Bivalves:

Cockle (Cardium spp.)

Crustaceans:

Marine shrimps (sp. indet.; Hawaii)

Portuguese crabs (sp. indet.)

Cephalopods:

Brief squid, calmar (Lolliguncula brevis)

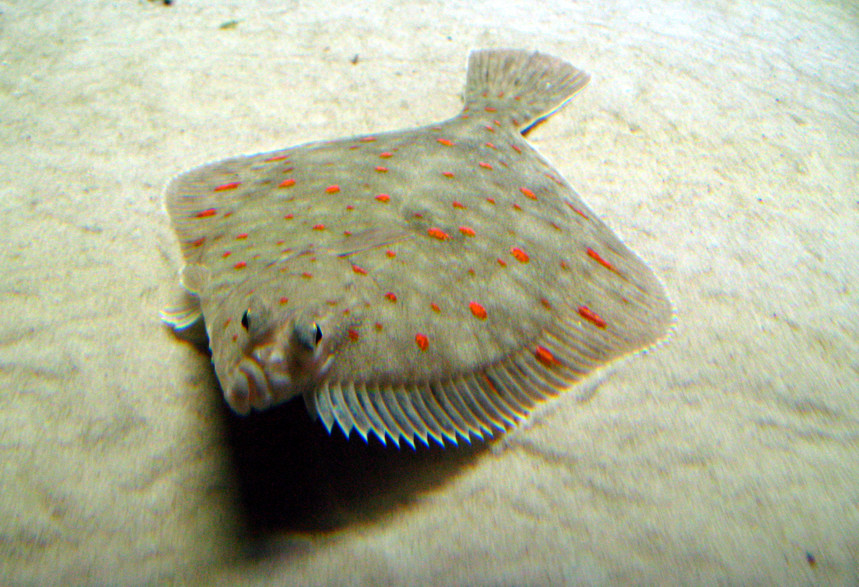

"All so far

examined flatfish like this European plaice (Pleuronectes platess)

are free of thiaminase."

"So far examined fishes from the family Gadidae like this Pollock (Pollachius

pollachius) are free of thiaminase and a good choice for pet fish

nutrition."

What to do with fishes not mentioned in the lists above?

Certainly not every fishy food is included in the lists above. For many

food items probably no data exists, yet. What you can do if you are

missing a food fish in the list is:

1. Find out the scientific name of the food fish and compare it to the

list again. Many fish are traded under obscure names.

2. Try checking literature for the food species yourself. Search engines

are your friends. (If you are successful, reporting it back could help

other hobbyists).

3. If you fail to find information, treat the fish in question as if it

contained thiaminase.

What obviously won’t always work is to see if the fish in question

belongs to the same genus or family as one or more of the fish enlisted

(e.g. with fishbase.org). Related fish from the same genus or family may

have a similar composition in terms of protein or fat, but the

thiaminase content sometimes seems to vary greatly even between species

within a single genus, and may even vary from population to population.

Little or nothing is known about the thiaminase content of some of the

small ornamental fishes usually used as feeders. However, goldfish and

minnows (including rosy red minnows) definitely contain thiaminase and

consequently make very poor choices as feeders. On the other hand, the

Poeciliidae (e.g., guppies, mollies, mosquitofish) are often recommended

as safe feeder fishes for predators because of their presumed to be low

thiaminase content. Despite claims among aquarists that guppies contain

thiaminase producing bacteria, I am not aware of any scientific study

demonstrating this to be the case. Since poecilids are grazers, an

uptake of thiaminase-producing cyanobacteria would be possible, though

less probable in a freshwater aquarium where a much smaller variety of

algae are likely to be present than in the wild.

Anecdotal evidence that the notoriously delicate Ribbon Eel can live on

a diet of mostly gut loaded black mollies for more than 15 years would

seem to suggest that poeciliids are largely thiaminase-free and make a

safe choices for feeder fish. Of course this depends on the quality of

the feeder fish being used, and cheap feeder guppies from pet stores

might not contain any thiaminase but could certainly contain all sorts

of pathogenic bacteria and parasites! So when poeciliids are described

as being among the best feeder fish, this depends on them being bred at

home and gut loaded with Vitamin B1-enriched foods, such as a good

quality flake food. Because poeciliids have a high tolerance for

saltwater (mollies in particular can be maintained indefinitely under

marine conditions) they are equally useful in saltwater tanks as in

freshwater aquaria. But this said, avoidance of feeders is the best

option in terms of cost, convenience and safety, and the use of feeders

should be limited to those few obligate piscivores that will not take

dead food or for the acclimation of newly introduced livestock prior to

being trained to accept dead or frozen foods.

“The thiaminase content of guppies is

unknown, but considered low or negligible, making them much safer to use

than goldfish or minnow feeders.”

How can I avoid the thiamine deficiency syndrome?

Prevention is the best way to “treat” the thiamine deficiency syndrome.

Things to avoid include:

1. Restrict feeding thiaminase containing fish to no more than 20%

of all meals.

2. Avoid feeding exclusively frozen bivalves or shrimps, because

these potentially have very high thiaminase content.

3. Avoid fish that was frozen for long periods (several months).

Things to do:

1. Keep the diet generally as varied as possible! Remember,

nutritional shortcomings in one type of food will be cancelled out by

the other types of food, so the more types of food, the smaller the

chance of nutrient imbalances.

2. Soak food in a vitamin product intended for pet fish prior to

feeding at least once a week, more often when feeding lots of shrimps

and bivalves!

3. Get small packages of food, and use them up quickly.

Final words

Thiaminase-containing food will not be instantly lethal to your pets,

but over the long term can result in a slow decline in health. Simple

measures and a little conscientiousness when buying and preparing food

is all that is needed to easily avoid Thiamine Deficiency Syndrome.

References

Anglesea, J.D. & Jackson, A.J. (1985): Thiaminase activity in fish

silage and moist fish feed. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 13: 39-46.

Deutsch, H.F. & Hasler, A.D. (1943): Distribution of a Vitamin B1

destructive enzyme in fish.- Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 53: 63-65.

Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations (1980):

ADCP/REP/80/11 - Fish Feed Technology. HYPERLINK

"http:]www.fao.org/docrep/X5738E/x5738e00.HTM#Contents"

http:]www.fao.org/docrep/X5738E/x5738e00.HTM#Contents

Greig, R.A. & Gnaedinger, R.H. (1971): Occurrence of thiaminase in some

common aquatic animals of the United States and Canada. Special

Scientific Report—Fish. U.S. Dept. Commer. Natl. Mar. Fish. Serv. 631:

1-7.

Hilker, D.M. & Peter, O.F. (1966): Anti-thiamine activity in Hawaii

fish.- J. Nutr. 89(4):419-421.

National Research Council (1981): Nutrient Requirements of Cold-water

Fishes. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

National Research Council (1982): Nutrient Requirements of Mink and

Foxes, Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

National Research Council (1983): Nutrient Requirements of Warm-water

Fishes and Shellfishes. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

National Research Council (1993): Nutrient Requirements of Fish.

National Academy Press. Washington DC, USA.

Royes, J.-A.B. & Chapman F.A.: Preparing your own fish feeds.-

University of Florida, 9 p. HYPERLINK

"http:]edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/FA/FA09700.pdf"

http:]edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/FA/FA09700.pdf

Scardi, V. & Magri, E. (1957): Thiaminase activity in Mytilus

galloprovincialis.- Boll Soc Ital Biol Sper. 33(7):1087-1089 (in

Italian).

Wistbacka, S.; Heinonen, A.; Bylund, G. (2002): Thiaminase activity of

gastrointestinal contents of salmon and herring from the Baltic Sea.-

Journal of Fish Biology 60(4), 1031-1042.

Yudkin, W.H. (1949): Thiaminase, the Chastek-paralysis factor.- Physiol.

Rev. 29: 389-402.

|