|

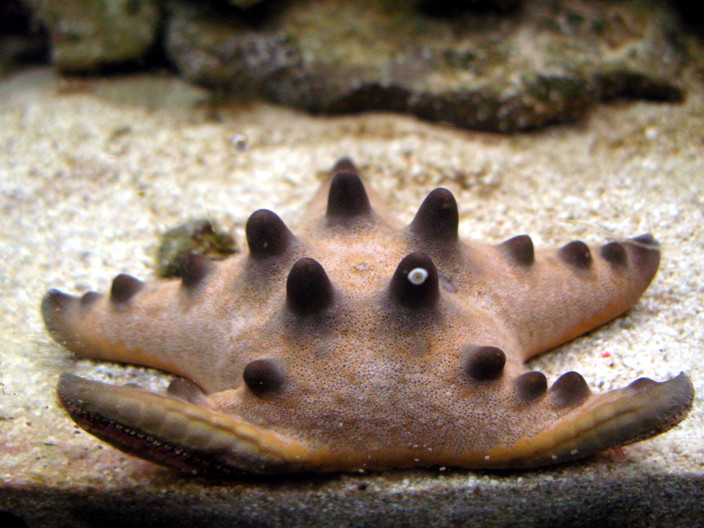

The Chocolate chip sea star (Protoreaster nodosus)

By Macro Lichtenberger

( click images for full size picture )

Common to both the pet fish and souvenir trade alike, the Chocolate Chip Starfish is well known among aquarists as well as to tourists and curio collectors. Despite this familiarity, this interesting and decorative species is much misunderstood. This article aims to summarize the biology and aquarium maintenance on the basis of observations of the species in nature and in captivity.

Natural occurrence

Chocolate Chip Starfish primarily inhabit sandy and muddy lagoons and seagrass beds, and are less common on the reefs themselves, preferring the back reef area. They are typically found in shallow water, at depths of 1-30 meters (3 to 100 feet); juveniles prefer even shallower water, and are most common at depths of less than 2 m (7 feet).

In their favored sea grass biotopes, Chocolate Chip Starfish can occur at densities of up to 30 specimens per 100 square meters (1100 square feet).

This species occurs widely across the tropical Indo-Pacific region. It is found along the East Africa coastline including the island of Madagascar; Sri Lanka; Indonesia; as far north as southern Japan and as far south as the tropical northern coast of Australia; it is also found around some island groups of the Southern Pacific.

Regionally it can be a very common starfish and is often collected, dried and sold as a souvenir.

The “chocolate chips” on the upper surface of Protoreaster nodosus can be rounded or pointed.

Description and distribution

The Chocolate Chip Starfish was among the first animals to achieve a formal scientific name, having been named by Linnaeus himself in 1758. It has several common names, being known primarily as the Chocolate Chip Starfish among aquarists but often as the Horned Starfish in the scientific literature and natural history books.

It is a member of the starfish family Oreasteridae, a group of starfish consisting of stout species with short, thick arms. Other members of the family are sometimes traded as aquarium specimens; these include the Red-Knobbed Starfish Protoreaster linkii and various species of Pentaceraster, sometimes called Knobby Starfish. Their aquarium care is similar to those of the Chocolate Chip Starfish, so much of what is said here applies equally to these starfish as well.

The eponymous “chocolate chips” or knobs are found only on the aboral surface, that is, the surface without the mouth. (Among echinoderm biologists, it is normal to refer to the upper and lower surfaces of the body as either the aboral or oral surface.) These knobs are believed to deter predators, perhaps by making the starfish too difficult to swallow whole; unfortunately for the Chocolate Chip Starfish, they do nothing to prevent humans from collecting them, the majority ending of these specimens ending up as dried souvenirs.

Other starfish from the family Oreastidae require similar care as the Chocolate Chip Starfish.

According to the scientific literature the central disk can reach a diameter of up to 12 cm (5 inches) and the arms a length of about 14 cm (5.5 inches). Consequently the entire starfish can reach a diameter of up to 40 cm (16 inches). These maximum sizes are rarely reached in either nature or in captivity though, most specimens getting no larger than 20-25 cm (8-10 inches) in diameter. In the Philippines, perhaps due to collecting pressure on the larger and more valuable specimens, Chocolate Chip Starfish larger than 14 cm (5.5 inches) are rare. The average diameter of adult specimens in the Philippines is about 10 cm (4 inches) and the average weight about 250 g (8.8 ounces).

Chocolate Chip Starfish reach sexual maturity at a diameter of about 8 cm (3 inches); at this point they are usually 2-3 years old. Most aquarium shops sell specimens about 10 cm (4 inches) in diameter, and these are about 5 or 6 years old. The bigger specimens sold measuring 14 cm (5.5 inches) or so are estimated to be around 17 years old.

It is unclear if the large specimens (40 cm/16 inches) mentioned in the older literature are really Chocolate Chip Starfish or something else. It could be that before they were seriously targeted by fisheries, Chocolate Chip Starfish in pristine habitats with lots of food could get very large indeed. Without selection pressure favoring specimens that became sexually mature when relatively small, the average adult size might have been larger than it is today. But it is also possible that collection by humans has had little impact on Chocolate Chip Starfish populations, and the big specimens mentioned in older books and scientific papers are wrongly identified starfish of other types.

Despite their name, the colors of Chocolate Chip Starfish can be quite variable. The ground color may be white, yellow, brown, red and even bluish, while the “chips” vary in color from grey to dark brown.

Physiology

The physiology of Protoreaster nodosus is similar to that of other starfish. Food and waste enter and exit the same opening, the mouth. Chocolate Chip Starfish eat by everting their orange-colored stomach out of the mouth and onto their prey. As the prey is digested, the stomach is slowly pulled back into the mouth. Because of the way they feed, it is quite easy to see what types of food they prefer, of which more will be said shortly.

Seawater is pumped into the vascular system by the madreporite, a small, wart-like structure on the aboral surface of the starfish usually located to one side of the central disk. The madreporite supplies the various canals that make up the water vascular system responsible for the movement of the mouth and tube feed. The water vascular system also works as the starfish’s circulatory system, doing many of the things that the bloodstream does in vertebrates.

If air gets trapped in the water vascular system, the starfish can find itself unable to move and eventually dies. Shallow water starfish do sometimes find themselves above the waterline in the wild, and do have the ability to close the madreporite and thereby prevent the air bubble problem. But this does assume they are not removed from the water too quickly, and aquarists should certainly avoid removing these animals from the water where possible, but if they must, they should do so slowly, exposing the arms to the air before the central disk, so that the starfish can react appropriately.

Chocolate Chip Starfish are found in the intertidal zone and may sometimes leave the water voluntarily, in which case they will have closed the madreporite themselves. Short term exposure to air and sunlight does not appear to cause these starfish any harm.

The madreporite is visible as a dark grey spot on the central disk and is used to regulate flow of water into the vascular system.

The water inside the vascular system of starfish is essentially identical to the seawater around them, and consequently sudden changes in salinity and temperature can be acutely stressful. It is essential that starfish are acclimated to the home aquarium slowly, so that they have time to adjust to differences in salinity and temperature compared to those experienced at the pet store. The larger the difference in salinity and temperature, the slower the acclimation process should be; using the drip method of acclimation, half an hour to an hour should be sufficient in most cases.

Curiously, these starfish possess some kind of memory, and are apparently are able to be trained to be fed at a specific point and at a specific time. In common with other starfish, they have a relatively simply nervous system without an obvious brain, so how they can exhibit such behavior remains unknown.

During the 1980s Chocolate Chip Starfish were at the center of research intended to benefit the biochemical industry. Several interesting chemicals were found in their bodies, including saponins, sterols and steroids. For whatever reason, this interest seems to have waned in recent years.

Reproduction

Chocolate Chip Starfish are dioecious, but the males and females cannot be distinguished without dissection. The two sexes occur in apparently similar numbers within each population.

Spawning takes place between March and May, usually in the deeper water parts of their range. Synchronous spawning of the entire population happens at full moon, coinciding with increased temperature and decreased salinity triggers. Spawning has been reported in aquaria as well as in the wild.

The eggs are small at about 0.2 millimeters in diameter. The larvae that emerge are planktotrophic, meaning that they spend some time in the plankton feeding on tiny organisms. Primarily because of this, they are notoriously difficult to raise in the aquarium. In the wild at least the floating larvae are found close to the bottom than at the surface of the sea, which is relatively infrequently seen among starfish larvae generally. Neither are the larvae as widely distributed as is often the case with starfish larvae. Chocolate Chip Starfish larvae stay in the plankton for 10-14 days until they finally settle onto the substrate and begin their exclusively benthic life.

In the wild at least, some starfish are able to survive being split into two or more pieces, each piece regenerating the missing arms or disk as required; it is unknown if Chocolate Chip Starfish have this facility.

Easy or difficult? – Nutrition gives the answer

Some hobbyists (and many retailers) consider this starfish to be hardy and easy to feed, while others state that its longevity in aquaria is poor (e.g. Goemans, 2007). I believe this is highly dependent of the aquarium system and available foods.

Unlike brittlestars, the bulky and stiff-bodied Chocolate Chip Starfish cannot squeeze into narrow gaps, so any food items in narrow crevices are lost for this species. To be of any use as a cleaner organism, the rockwork needs to be fairly open. Neither does this starfish consume most types of nuisance algae or the bacterial films such as cyanobacteria that sometimes develop in aquaria.

In nature Chocolate Chip Starfish consume mostly the tiny meiobenthic animals found between sand grains as well as microbial and algal films (Scheibling & Metaxas, 2008).

However, in captivity Chocolate Chip Starfish have been reported to eat a very wide variety of sessile and slow moving organisms, including sponges, soft corals, anemones, bivalves, snails, bivalves, bryozoans, feather duster worms, sea urchins, smaller starfish, and even small fish if they can catch them. They also consume organic detritus including feces, carrion and decaying sea grass.

Nonetheless, given their preferences in the wild, it is probable that these large foods are, to some degree at least, alternatives to what they should really be eating.

Chocolate Chip Starfish consuming an algae wafer with its extended stomach.

Chocolate sea stars do best in systems with high water quality, but enough detritus and small benthic animals for them to feed. Tanks without skimmers or mechanical filters seem to be ideal, but these are more difficult to keep in top condition with regard to water quality, and can only be recommended to the advanced hobbyist. Deep sand beds commonly result in abundant benthic invertebrate life and, if well populated, will provide lots of the types of prey Chocolate Chip Starfish like to eat. FOWLR systems can also work well, particularly when these contain reasonably large quantities of macroalgae.

On the other hand, spotlessly clean stony coral reef systems do not resemble their natural environment at all, and usually have too little food of the right types to keep Chocolate Chip Starfish healthy. Equally inadequate are fish-only tanks without much surface area for them to graze on, a minimal population of small benthic invertebrates, and a high nitrate concentration.

General maintenance

The typical small to medium-sized Chocolate Chip Starfish traded can be kept in tanks as small as 50 gallons in size, with the proviso that pristine water quality can be maintained. Larger specimens measuring 25 cm (10 inches) upwards will need a bigger tank, at least 100 gallons in size and preferably more.

General water parameters recommended are similar to those of other tropical marine invertebrates: specific gravity 1.022 to 1.027; temperature 22 to 27 degrees C (72 to 81 degrees F); pH of 8.0 to 8.4; and nitrates substantially below 20 mg/l.

My own approach to this species is to keep them in a tank with live rock; a well-populated deep sand bed about 4.5 inches in depth; various red and green macro algae species rather than corals; and only a few medium-sized fishes that prefer larger foods than those consumed by these starfish (i.e., no grazers or plankton eaters).

The tank does not have either a skimmer or mechanical filtration. The Chocolate Chip Starfish feed mainly on biofilms in the tank, including those at the waterline. They also consume the small benthic invertebrates and leftover fish food not taken by the fish, including things like chopped mussels and white fish fillet.

My specimens have consumed soft and stony corals, but do not appear to damage any of the decorative sponges in the tank, and only partially digested a hydroid colony. Strangely, while my specimens did not eat Aiptasia anemones, they did eat some Thalassianthus anemones, which also have quite potent stings.

One sign that this system works well for the species is the speed with which one Chocolate Chip Starfish placed in this tank healed from a wound sustained following a tumbling rock incident in another tank. When starfish are maintained in less than optimal conditions they tend to show much less resilience, despite wild starfish being famed for their regenerative abilities. Growth rate is slow but steady, in keeping with what is observed among Chocolate Chip Starfish seen in the wild.

In tanks with mechanical filtration, skimming and populations of fishes likely to compete with them for food, Chocolate Chip Starfish can be maintained only by putting out food specifically for them. This can be done by placing the starfish on top of morsels of food such as algae wafers once or twice a week. Although this may work, it is less than ideal because the starfish cannot choose its diet as it would in the wild, and nutritional imbalances are consequently more probable.

Disease

Chocolate Chip Starfish are able to recover from severe wounds given ideal water quality and an adequate food supply, but under less than perfect conditions they quickly fall prey to heterotrophic bacterial infections that infect small scratches and other wounds.

Maintenance in groups

What about keeping Chocolate Chip Starfish as a group? In the wild, when scientists have deliberately placed extra individuals within a given area, they have eventually spread themselves out again, restoring their normal population density.

If this is an indication of territoriality or a need for living space, it is probably wise not to permanently overstock the aquarium. A population density of one specimen per 3 square meters (about 33 square feet) seems to be normal in nature, and that is rather more space than we would tend to allow them in the aquarium. Tanks less than 3 m (10 feet) in length and 1 m (3 feet) in width should be considered the minimum amount of space for two or more specimens.

Enemies

Although starfish are fairly well armored and generally ignored by most fish, several types of fish will view them as food, including triggerfish, pufferfish, boxfish and parrotfish. Not all species in these groups will eat them, but many will, and it is up to the aquarist to research the dietary preferences of the fish in question before combining them with Chocolate Chip Starfish.

Chocolate Chip Starfish will consume smaller starfish, including their own kind; this specimen is eating an Asterina sp. cushion starfish

Among the invertebrates, large starfish frequently consume much smaller starfish given the chance, and Chocolate Chip Starfish may be cannibalistic towards each other, so only similarly sized specimens should be kept together. Some shrimps are notable predators on starfish, particularly those in the family Hymenoceridae, including the often-traded Harlequin Shrimps Hymenocera picta and Hymenocera elegans.

Tank mates

In the wild Chocolate Chip Starfish are commonly found in association with the glass shrimp Periclimenes soror. These shrimps live on the starfish and even adjust their colors so that they match their host as unobtrusively as possible. Since lots of fish eat shrimps, but rather few eat starfish, hiding away on a starfish is probably quite a useful trick.

Although this co-existence (or even possible symbiosis) would be a very worthwhile subject for the advanced aquarist interested in marine ecology, Chocolate Chip Starfish are almost always imported without these shrimps. Furthermore, Periclimenes soror are only rarely available in the trade because they are eaten by most reef tank fish, so have little value as reef tank residents in their own right.

The other major group of commensals found living alongside these starfish are various polychaete worms, the worms aquarists often call bristleworms. Given the suspicion directed at polychaete worms by most aquarists, I doubt that these worms are either likely to appear on traded Chocolate Chip Starfish or to be tolerated for long should they appear.

Closing words

In an adequate tank the Chocolate Chip Starfish can be a hardy as well as decorative pet. Looked after properly, surely it is a much more delightful sight than a dried specimen sitting on a bookshelf?

Chocolate Chip Starfish do well in FOWLR systems with macro algae or seagrass, and can make excellent pets.

Literature

Erhardt, H. & Moosleitner, H. (1997): Meerwasser Atlas, volume 3, 1328 p. (in German).

Goemans, B. (2007): Marine invert of the month - Protoreaster nodosus (Linnaeus, 1758).- TFH, 56(1) September 2007, p. 76.

Bos, A.R.; Gumanao, G.S.; Alipoyo, J.C.E.; Cardona, L.T. (2008): Population dynamics, reproduction and growth of the Indo-Pacific horned sea star, Protoreaster nodosus (Echinodermata; Asteroidea).- Marine Biology, 156(1), p. 55-63.

Scheibling, R.E. & Metaxas, A. (2008): Abundance, spatial distribution, and size structure of the sea star Protoreaster nodosus in Palau, with notes on feeding and reproduction.- Bulletin of Marine Science, 82(2), 221-235.

Riccio, R.; Zollo, F.; Finamore, E.; Minale, L.; Laurent, D.; Bargibant, G.; Pusset, J.(1985): Starfish saponins 19. A novel steroidal glycoside sulfate from the starfishes Protoreaster nodosus and Pentaceraster alveolatus.- Journal of Natural Products (Lloydia), 48(2), p. 266-272.

Crandall, E.D.; Jones, M.E.; Munoz, M.M.; Akinronbi, B.; Erdmann, M.V.; Barber, P.H. (2008): Comparative phylogeography of two seastars and their ectosymbionts within the Coral Triangle.- Molecular Ecology. 17(24), p. 5276-5290.

Hartmann-Schröder, G. (1984): 2 new commensal polychaeta of the genus Hololepidella polynoidae from the Philippines.- Mitteilungen aus dem Hamburgischen Zoologischen Museum und Institut, 81, p. 63-70.

Chocolate Chip Stars on WWM

Related FAQs:

Chocolate Chip Stars,

Chocolate Chip Stars 2,

CC Star Identification,

CC Star Behavior,

CC Star Compatibility,

CC Star Selection,

CC Star Systems,

CC Star Feeding,

CC Star Disease/Health,

CC Star Reproduction,

Sea Stars 1,

Sea Stars 2,

Sea Stars 3,

Sea Stars 4,

Sea Stars 5,

Seastar Selection,

Seastar Compatibility,

Seastar Systems,

Seastar Behavior,

Seastar Feeding,

Seastar Reproduction,

Seastar Disease, Asterina Stars,

Crown of Thorns Stars,

Fromia Stars,

Linckia Stars,

Linckia Stars 2,

Sand-Sifting Stars, Related Articles:

Sea Stars, Sand Sifters, An Introduction to the Echinoderms: The Sea Stars, Sea Urchins, Sea Cucumbers and More... By James W. Fatherree, M.Sc.

Genus Valenciennea Gobies, Deep Sand Beds,

Live Sand,

Biofiltration,

Denitrification,

Live Sand,

Live Rock,

| |

|

|