|

Related FAQs: Cool./Cold Marine Systems,

Chillers/Chilling & FAQs, FAQs 2, &

FAQs on: Cool./Cold Marine Set-Up, Cold/Cool Water System Filtration,

Cold/Cool Water System

Skimmers, Cold/Cool Water System

Lighting, Cold/Cool Water System

Stocking, Cold/Cool Water System Maintenance

& FAQs on: Chiller Rationale/Use, Selection, DIY, Installation, Maintenance, Fans For Cooling, Troubleshooting, & FAQs on: Coldwater

Sharks, Leopard Sharks,

Heterodontus, Fish-Only Marine Set-ups,

Fish-Only Marine Systems

2, FOWLR/Fish and Invertebrate

Systems, Reef Systems, Small Systems, Large

Systems, Marine

System Plumbing, Biotopic presentations,

Related Articles: Marine

Planning, Getting Started with a Marine Tank By

Adam Blundell,

MS, Coldwater Sharks, Leopard Sharks, Port Jackson Sharks, Fish-Only Marine Set-up, FOWLR/Fish and Invertebrate Systems,

Reef Systems, Small Systems, Large

Systems, Plumbing Marine Systems, Refugiums, Moving Aquariums, Marine Biotope, Marine Landscaping, Fishwatcher's

Guides, Controllers,

Setting Up a California/Pacific

Coldwater Aquarium

|

|

|

By Bob Fenner

|

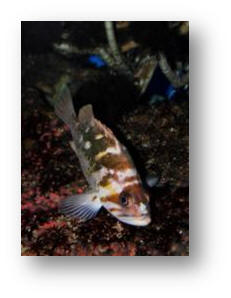

A tasty rockfish at SIO's Birch

Aq. |

The

more you look, the more there is to see. This certainly applies to the

myriad possibilities of marine aquarium systems possible to us as

aquarists. Biotopes of varying current, lighting,

food-availability-make-up; specialty tanks emphasizing one species or a

group like SPS or Leather Corals; full-on breeding rigs for producing

specific algae, invertebrates and fishes Whats often left out of

discussion are non-tropical possibilities; yes, cool to cold-water

set-ups. After all, the majority of the worlds oceans are decidedly NOT

tropical. Whats more, living in the United States, we have two coasts

to choose from with a plethora of life forms to enjoy and study

occupying them. Here well explore the basics of what it takes to have a

local /coldwater system, including gear, set-up, livestocking, with

special note re a popular goby.

Steps to Completion:

A Plan:

How are you going to know where youre going w/o a

plan? I cant emphasize enough how important it is to study up, gather

data, other folks input before starting actual purchase of gear with

coldwater systems. IF your tank is not matched to the chiller,

filtration, circulation, lighting you will fail. So, the place to start

is what do you either want to keep species wise, or display/theme-wise

and next, what do you want to do with them/it?

Gear/Set up:

Chillin

Lets

first talk about chillers: All cool to cold water set ups require a

chilling mechanism. Even the largest volumes will drift too much

thermally w/o a thermostatically controlled device to keep your water

about the right temperature. For the majority of set-ups commercial

chillers resemble and operate something like a home refrigerator, with

a compressing pump pressurizing a coolant to make it convert from a gas

to a liquid, an area allowing for expansion and hence cooling, and some

heat exchanger providing for this loss of energy to transfer to the

circulated system water itself. The last can include drop in coils that

are inserted in tie-in sumps for the most part. And it should be

briefly mentioned that there are other types of coolers, cooling that

is employed at time, including ground/earth and other heat exchanger

technology, as well as more technical gear. These other means are for

either very large or quite small (a few tens of gallons)

systems.

Selecting a chiller is a straightforward

proposition. Happily, in the age of the internet there are quite a few

dependable websites and bulletin boards where you can query other

actual users which makes, models theyve found to be of good use

(reasonable purchase and operational cost, longevity); and all such

manufacturers have readily available selection charts, often on the Net

as well, that can be assessed to determine what size (in

fractional/horsepower) youll need considering volume of the system and

draw-down (the difference between likely highest ambient temperature

and your desired system/tank water temperature). In actually picking

out a chiller size, I encourage folks to get the next one up to give

them a bit of operational margin, as well as provide for the very real

possibility of their upgrading to a bigger volume system in future.

Your chiller needs careful placement. Like your

home fridge, the heat-dissipating coils of the unit need to be

periodically vacuumed to remove accumulating dust, and some space needs

to be left about the unit for air-circulation and the occasional need

to perhaps get in around it, maybe even remove it for servicing. Do

make sure and place the chiller near an electrical outlet w/ sufficient

spare amperage, and be aware that some units produce noticeable sound

when operating.

Cold-water Tanks:

To

save money and discount condensation, either your tank should be

especially thick-walled, or insulated. Early commercially made chilled

aquatic systems incorporated a double-paned viewing (front) panel with

a sealed in air space and purposeful desiccant (Calcium Chloride in

some cases) to absorb the water vapor twixt the panels during

construction. If you use just a stock set of specifications (strength

only) you may well be disappointed in how easily moisture builds up on

the outside panels, obscuring the view, wetting the surfaces

underneath, and perhaps most disturbing, driving up your electrical

bills from over-running your chiller.

A

regular tank can and should be insulated, and the top covered to

prevent thermal leaking. A simple approach for the sides, back and

bottom is to use a glue to attach cut sheeting of Styrofoam. These

supplies are easily sourced at large hardware stores. Similarly, any

sump/refugium employed should be covered. You may be fortunate to have

relatively low humidity in your area much of the time, but if you find

theres too much, too often a coating of condensation on the front

viewing panel, siliconing in another in front of it/ with a small layer

of CaCl2 at the bottom space may be worthwhile.

Filtration:

Filtering coldwater systems should encompass brisk water movement,

complete circulation, and a good deal of mechanical (particulate)

screening. Ive kept large systems with just multiple hang on power

filters, w/ and w/o skimmers, and using or not, any chemical filtrant/s

whatsoever. Remember, the key with these systems is keeping them cold,

not-overfeeding (which again is reduced with the temperature), and

relying on good-sized water changes as the primary means of keeping

water quality stable and optimized. Some commercial designs have

utilized pressurized filter modules, but I really dont like these for

the amount of labor involved keeping them clean, and the power/cost of

running the pumps to squeeze the water through their media.

Lighting:

Illuminating these systems does not need to be a major production like

tropical reef systems. Better to utilize some sort of middle of the

road boosted fluorescent technology than anything else that produces

too much waste heat like metal halide, unless your system is more than

a couple feet in water depth. A good idea to use timers to regulate

photoperiod, and its fine to leave the lights on ten-twelve hours a

day, given regularity.

Water:

Many

hobbyists, and even institutions located on the beach utilize synthetic

water, vs. natural. They do this for convenience, greater longevity/use

of the man-made product, and to reduce the likelihood of introducing

unwanted critters, pathogens and pollutants. Alternatively, there are

vendors of filtered natural seawater some that will deliver to your

site, and places where folks can easily drive up and fill their

containers with (sand/physical) filtered seawater for free. IF you opt

for this latter approach, I STRONGLY encourage you to adopt a strict

protocol of pre-treatment and storage of the water ahead of use. Some

folks just place it in the dark for a couple weeks, decanting the

water, leaving whatever mulm on the bottom to discard. Others utilize

chlorine/bleach as a biocide, removing this a few days later w/

dechlorinator to assure they exclude unwanted biota.

Cloze:

Amongst the challenges/joys of development as an aquarist is the

exploration of different types of systems, biotopes and the life that

can be kept in them. Coldwater systems should definitely be

experienced; for their beauty, grace and potential learning. IF you

live along a cool/er water coast, DO consider checking them out.

Sidebars

Stocking

Pacific Coldwater Tanks:

There is some good to great news re stocking these systems and some not

so great. The positive is that you can really load them up with life

compared w/ tropical tanks. This greater latitude is due to reduced

metabolic rates from depressed ambient temperature, as well as enhanced

gas solubility in such settings. The negative mentioned is a matter of

availability. There are a few specialty collectors (Quality Marine is

an L.A. wholesaler who deals with these a bit) who provide wild-caught

algae, invertebrates and fishes from the U.S. west coast. Hence, for

the most part, folks are limited to what either they can collect (not

hard to do w/ some minimal gear and licensing) or have other

friends/aquarists/fishers gather for them.

This being stated, Ill give you a glimpse of what

is here, has been proven of use:

|

Macro-Algae: There are a couple of handfuls of

local species Ive seen offered for sale in some shops in S. Cal..

Amongst the Greens (Chlorophytes) they include Codium (dead sailors

fingers), which doesnt generally do well, and the more useful Ulva

(shown below). Browns (Phaeophytes) involve a few Fucus/Fucales

species (one shown), and Reds (Rhodophytes) abound as branching

corallines (pictured) as well as very familiar encrusting forms. As

with tropicals, much of useful algae will come with healthy local

live rock, not requiring direct purchase.

|

|

|

|

Some Invertebrates: From time to time you can

find Pacific coast anemone species, some snails and echinoderms

offered for sale. All too infrequently theyre not labeled properly;

requiring chilled systems. Some examples: The Giant Green Anemone,

Anthopleura xanthogrammica, a few to several inches in diameter

depending on how far south to north it was collected, and the

deeper water Strawberry Anemone, Tealia lofotensis, and beautiful

genus Metridium (all pictured)

|

|

|

|

One last Cnidarian we should list is the

Corallimorph, Corynactis californica; not only a darling of coastal

public aquarium displays, but actually quite easy to keep and

culture. Oh, and there is a bunch of other stinging-celled life off

the coast, some of it, like jellies of various sorts, possibly

showing up via strobilization off your life rock; but much of this

has proven difficult to keep.

|

|

|

|

Some Mollusks sold in the ornamental trade

come from off shore California. Moon Snails (Polinices) and Bubble

Snails (Bulla) rarely live for any time in captive settings;

however cultured abalone, particularly the Black (Haliotis

cracherodii), and Red (H. rufescens), and Keyhole Limpet

(Megathura) are winners for larger systems w/ abundant algal forage

(pictured)

|

|

|

|

Of the spiny skinned life off the west coast,

most gets too large for all but the biggest (hundreds of gallons)

of hobbyist-sized systems. Of the best are genus Pisaster Seastars,

Patiria (Batstars) and the Purple Sea Urchin, (Strongylocentrotus

purpuratus)

|

|

|

|

There are more than 500 species of nearshore

marine fishes off our west coast, with most being or getting too

big, rambunctious, or just being behaviorally poorly

adapted/adaptable to captivity. Of the ones that you can buy

(collected out of Mexico, not the U.S., where its taking is

outlawed), the giant damsel called the Garibaldi is no doubt the

most desired. Juvenile and adult coloring shown. Another favorite

family of use is the livebearing Surfperches (family Embiotocidae).

There are numerous gobies, Sculpins and relatives, rockfishes and

much more that can work for fish stocking Pacific coast

Coldwater systems. My best advice is to spend some time perusing

the Web, books that detail public exhibits on display in aquariums

in the area. Also, do please see Tom Niesens work and Miller and

Leas Bulletin 157 for valuable input life here. (See

biblio.)

|

|

|

|

In the brief space allotted, I would also like

to mention the not-uncommon selling and keeping of two of our more

common shark species, the California Horned Shark (Heterodontus

francisci), and Leopard Shark (Triakis semifasciata). These and the

one Moray off our coast, the Green/California, Gymnothorax mordax,

are really animals for only the most experienced and dedicated of

aquarists; requiring huge volumes and considerable expense in their

keeping.

|

|

|

Stocking is done as with any captive aquatic

system; with preparation and testing to assure nitrogen cycling is

complete, in steps not to overwhelm beneficial microbial populations. I

start new systems near the high temperature-wise that Ill be keeping

them to promote the process, and place some live rock (often with all

organisms intact rather than removing macroalgae et al.) in three or

four every two-three week interval steps to allow for die-off and large

water change effects. The break in and livestocking steps entail a few

months time; definitely more than warmer water set-ups, due to the

reduced chemical/biological activity of lower temperature.

Sidebar:

About the Catalina Goby:

Though too often sold as a tropical or even cool-water species, the

Catalina Goby is decidedly cold water (50s to low 60s F.) species;

living a much shortened, tenuous period if kept in warmer water.

|

The Blue-Banded or Catalina Goby, Lythrypnus

dalli (Gilbert 1860), is a real beauty with its brilliant red body

and electric blue vertical lines. Its natural distribution is the

two California (Baja, Mexico and U.S.) Pacific coasts. Because it

is not a true tropical, it lives only a short while in water in the

70s F. Specimens collected in the summer months live a bit longer,

but rarely more than a year.

|

|

|

Bibliography/Further Reading:

Burgreen, Warren W. 1972. An inexpensive cold water aquarium. Marine

Aquarist 3(2):72.

Ellis, Gerald R. 1982. Keeping temperate marines. FAMA

6/82.

Glodek, Garrett S. 1990. Coldwater marine aquariums. FAMA

9,10/90.

Goldstein, Robert J. 1992. Cold-water aquaria; making a big splash

with consumers. Pet Age 4/92.

Miller, D.J. and R.N. Lea. 1976. Guide to the coastal marine fishes

of California:

California fish bulletin number 157

Niesen, Thomas M. 1982. The Marine Biology Coloring Book. Harper

& Row, Publishers, NY.

Robertson, Graham C. 1975. Collecting and keeping temperate marines.

Marine Aquarist 6(6):75.

Wrobel, David J. 1987. Keeping native marine fish in the home

aquarium. FAMA 12/87.

Wrobel, David. 1992. The temperate marine aquarium. TFH

6/92.

Wrobel, David. 1992. Chilling your aquarium; how to control

excessive water temperatures. AFM 12/92.

Are there any commonly available "tropical" marine fish that

actually prefer temperate 62 degree F water?

12/3/13

<Mmm; yes... Catalina gobies (Lythrypnus), Blue-spotted Jawfish...>

I live in Florida and have a nice little ten gallon planted freshwater

tank and four tropical reef tanks ranging from a 6 gallon Fluval Edge

with soft corals of various types (although my pulsing Xenia is starting

to run away in that tank....Grrr)

<Trim it back and vac regularly>

and a yasha goby with its pet/worker slave shrimp to a 30 gallon Biocube

with a variety of sps and Lps hard corals and an assortment of

aggressive fish that were carefully introduced and have been doing

"swimmingly" for a couple of years (a neon Dottyback, a yellowtail

damsel and a falco Hawkfish all of which have their own territories and

there are no squabbles (damsel high, hawk middle and dotty skulking

along the ground and in various caves I've set up) even during feeding.

So.....my question has nothing to do with the above humblebrag (which is

really just to show I have some at least limited experience in your

world). However, since then we have bought a 20 gallon coldwater

marine setup as my wife and I have spent a fair amount of time on the

Left Coast recently despite living in Florida and have seen how in the

right hands a coldwater tank can be just as beautiful (or at least

almost) as a typical tropical reef tank.

<Oh yes>

In place of corals, we have some stunning quickly growing colonies of

jewel "anemones" in the Corynactis genus (a variety that is highlighter

yellow with red tentacle tips, one that is a bright neon green with pink

tips and the more common "strawberry" variety that are pink with purple

tips) and an assortment of true anemones (plumose anemones or Metridium

genus in white, orange and a pretty rare lime green variety; a couple of

the beautiful in small doses but very common aggregating anemones

Anthopleura elegantissima; two small green moonglow or burrowing

anemones Anthopleura artemisia; a burnt orange beadlet anemone Actinia

equina; and a "true" strawberry

anemone Actinia fragacea. The tank looks

great although it's a little sparse as it will probably be 6 months to a

year or more before the Corynactis colonies grow in sufficiently to

cover the rockwork.

In addition to the true anemones and "anemones", we've got a basic

assortment of coldwater cleaner snails including the black turban snails

Tegula funebralis that are frequently seen in Florida LFS as reef

cleaners; purple olive snails Olivella biplicata;

<Just picked up a nice shell of which at Volleyball last wknd...

imported sand here in San Diego... beach to bay>

and periwinkles Littorina littorea. Other members of the cleanup

crew is a fat and healthy eccentric sand dollar/biscuit urchin

Dendraster excentricus and five micro hermit crabs supposedly in the

Pagarus genus (although one is getting much bigger than the others so

I'm keeping my eye on him in case he turns out to be too big and

aggressive). At the moment for our "display" active critters we

have a Catalina Goby Lythrypnus dalli;

<Oh!>

a fluffy sculpin Oligocottus snyderii; a stout shrimp Heptacarpus

brevirostris and a porcelain crab Petrolisthes eriomeris.

So far everything is doing well and is fat and healthy except the

plumose which refuses to come out in the daylight and a small spot prawn

and previous Catalina Goby that was living in the tank with the other

aforementioned fish. The other Catalina goby and small spot prawn

were fat, eating well and both completely disappeared with no signs of

illness, distress or aggression from other creatures. I assume

they both dove head first into one of the true anemones despite the

retailers assurance they "live with anemones and would never get

caught".

<Wrong>

My dilemma and the reason for the extensive write up is that I would

like to get more activity in the tank and miss the "free swimming" fish

I have in most other tanks. The only true coldwater fish small

enough for my tank are all bottom dwelling Sculpins and gobies or else

incredibly rare in the trade micro filefish and small lump suckers that

go for hundreds of dollars per fish. However, as I live in Florida

I can't keep the "coldwater" tank at 50-55 like they do at public

aquariums as the condensation becomes too much in an ordinary Florida

home. So I keep it at a balmy for them 62 degrees and it hasn't

seemed to noticeably affect anything (unless that's the reason for my

plumose's shyness).

Can you think of any small "tropical" fish that would be happy in 62

degrees AND not be stupid enough to dive head first in the nems?

<Mmm, well; I wouldn't add anything more to this small volume... IF you

lived locally, I might buy a fishing license, do a bit of tidepool

collecting... some small (young) Surfperches, perhaps a Girella... even

a tiny Hypsypops for a while would be fab. Bob Fenner>

Re: Are there any commonly available "tropical" marine fish that

actually prefer temperate 62 degree F water?

12/3/13

Thank you for the response. That's unfortunate as I would like

something in the top and middle portions of the tank free-swimming.

<Ah yes; many possibilities. Do you have a copy of Miller and Lea,

bulletin 157? Any of Sam Hinton et al.s works re the W. coast? BobF>

Re: Are there any commonly available "tropical" marine fish that

actually prefer temperate 62 degree F water?

12/3/13

No but I will see if I can track some down and review. Thank you.

<Ahh, I look forward to our future communications. B>